By Anabel Costa

Internationally noted science writer and curator Margaret Wertheim began her “Crafting Mathematics” virtual seminar on Monday with the question: “Does a sea slug understand hyperbolic geometry?”

“To give you a spoiler, my answer is going to be ‘yes’,” she said.

The seminar was hosted by the Media Arts and Technology graduate program at UC Santa Barbara, which probes the intersection of science and art much as Wertheim has done by authoring six science books at the same time as creating art that has appeared in numerous museums, including the Smithsonian.

Science writer and artist Margaret Wertheim uses the craft of crochet to make sculptural representations of coral reefs.

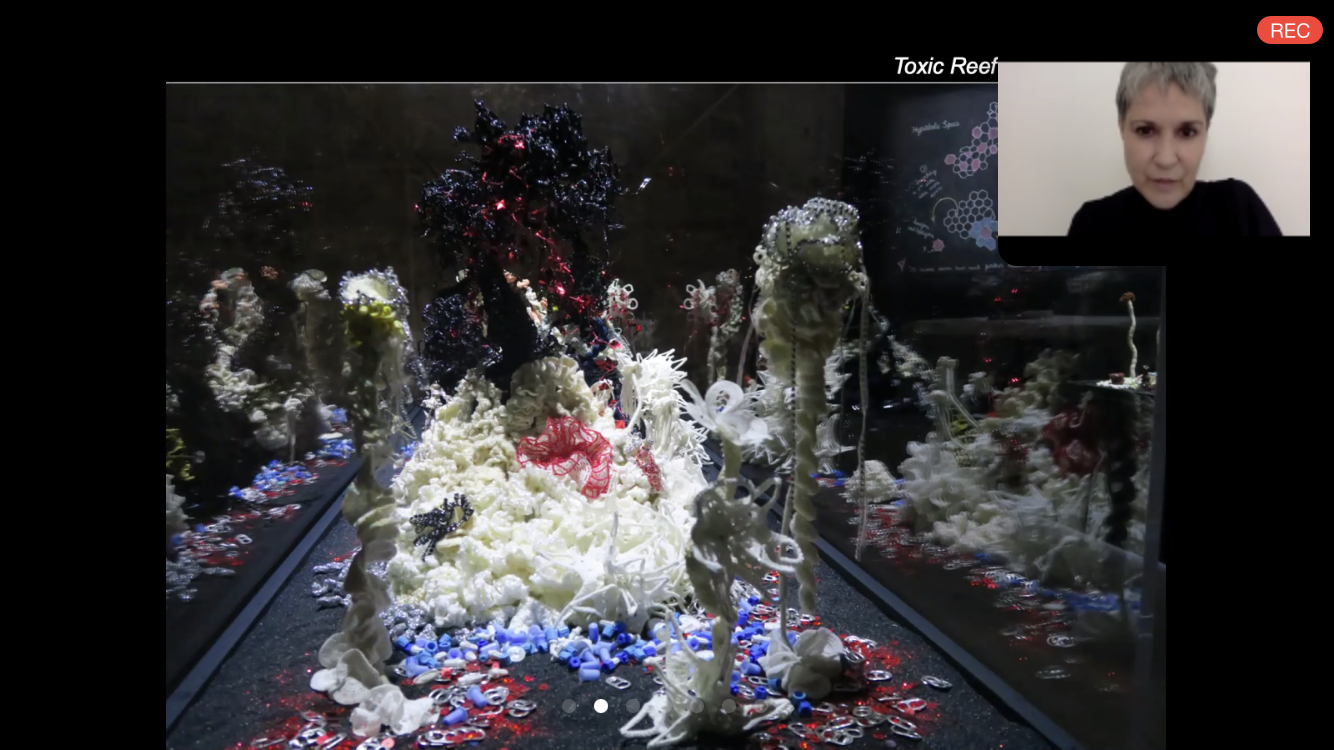

Wertheim grew up in Australia near the Great Barrier Reef with her twin sister Christine, where she became quite familiar with the lives of sea slugs. Even so, asserting that invertebrates could be mathematically-inclined is a bold claim. But she makes a convincing case — and she does it with a crochet hook. With nothing more than a hook and yarn, she and her teams have created entire coral reefs, and made the spectrum visible – and touchable - from healthy reefs to what she calls her “toxic reefs” that show the devastation of climate change.

In 2003, the Wertheim sisters founded The Institute for Figuring, a Los Angeles-based organization dedicated to the poetic and aesthetic dimensions of science, mathematics and engineering. There, they host the Crochet Coral Reef project. “The project exists at the nexus of art, science, math, climate change, and community engagement,” Wertheim said.

While she went to school to study sciences and her sister studied arts, they don’t see the two practices as so different. In fact, Wertheim argues that the methodologies of science can be used in art, and vice versa. Thus, Crochet Coral Reef was born as an artistic response to climate change.

The Crochet Coral Reef project has spread to communities in 12 different countries and has over 10,000 participants.

“Just as a computer uses code to make it function, so does crochet,” said Wertheim. By following a specific pattern, Wertheim is using this “code” to create the frilled forms of corals and other crenulated marine organisms. Moving stitch by stitch, her process emulates how coral reefs are actually formed.

She considers her work a craft-based evolutionary practice. These intricate and expansive wooly representations have been widely exhibited around the world, and the practice has been shared with communities in 40 different locations across 12 countries.

Those involved in the project have crocheted white reefs that show the devastation of coral bleaching caused by global warming, and they have even crocheted real plastic and detritus from the Great Pacific garbage patch into their works — ones they call “toxic reefs.” Critics have called the toxic reefs ugly, to which Wertheim responds that beautiful reefs are what exist naturally, while the plastic ones are a representation of human-caused destruction.

Margaret Wertheim’s Crochet Coral Reef project creates white reefs to showcase the devastation of coral bleaching.

But what does this have to do with hyperbolic geometry?

In her talk, Wertheim described the three types of geometry: euclidean, spherical, and hyperbolic. Euclidean space is flat and has zero curvature, while spherical space is round and has positive curvature. Hyperbolic space however, was only discovered about 200 years ago, and before then, mathematicians thought it to be impossible. Hyperbolic structures look like Wetheim’s crocheted corals, and they look like sea slugs. Hyperbolic space has negative curvature, and can be likened to the geometric equivalent of negative numbers.

For corals and sea slugs, hyperbolic geometry works in their favor by maximizing their surface area, making it easier and more efficient to absorb nutrients from their surroundings, and to propel themselves through the water. She believes such structures were evolutionarily encoded into their bodies and can be considered a form of knowing.

But it’s not just corals and sea slugs — there are many biological manifestations of hyperbolic structures. “As it turns out,” said Wertheim, “nature has quite a love affair with hyperbolic forms.” Although they may not be able to pass a university test in mathematics, certain types of flowers, and even lettuces, grow in a way that exhibits a knowledge of hyperbolic geometry.

Work from Margaret Wertheim’s Crochet Coral Reef project has been showcased in museums and galleries around the world.

Wertheim says that hyperbolic geometry can even tell us something about the structure of the cosmos. “If there is flat, spherical, and hyperbolic space, what does that mean for the geometry of the universe?” It’s a big question to answer in one hour over Zoom, but it’s part of what the Wertheim sisters seek to understand and teach through their crochet practice; they use craft to embody mathematical learning, and to find tactile truth in abstract equations.

Anabel Costa is a fourth year Theater major. She is a Web and Social Media Intern for the Division of Humanities and Fine Arts.