By Romy Hildebrand

Award-winning author Jesmyn Ward crafts her characters in order to explore trauma and how to survive it, she told a UC Santa Barbara audience last week.

“My characters are trying to figure out not only what it means to witness trauma, but also how to survive it, how to work through it, and how to integrate it into their understandings of who they are,” she said. “How these stories are a part of them and how this then changes them.”

Ward is this year’s Writer-In-Residence in the Diana and Simon Raab Writer-in-Residence Program, which aims to “bring distinguished practitioners of the craft of writing to the UCSB community.”

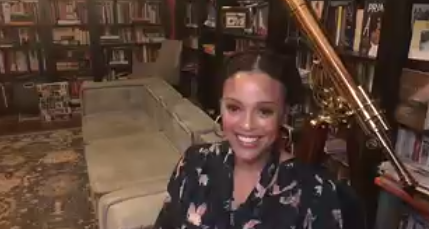

The 2020 Diana and Simon Raab Writer-In-Residence Jesmyn Ward, center, and IHC Director Susan Derwin, upper right, discuss Ward’s exploration of trauma in her work, with an ASL interpreter Katie Voice over Zoom.

She was speaking of characters from her books Sing, Unburied, Sing and Salvage the Bones, both of which have won the National Book Award, in a conversation with Susan Derwin, director of the Interdisciplinary Humanities Center. The virtual event was co-sponsored by the Writing Program as part of the IHC’s Living Democracy series.

Ward’s work encompasses fiction, nonfiction, and memoir, and was called “raw, beautiful, and dangerous,” by the New York Times Book Review.

Jesmyn Ward, UCSB’s 2020 Diana and Simon Raab Writer-In-Residence and author of Salvage the Bones, The Men We Reaped, and Sing, Unburied, Sing.

Ward described how her characters work through their traumatic experiences and find meaning through their journeys. By telling their stories they find a certain tenderness for and awareness of who they are, she said.

Salvage the Bones follows the story of Esch, a young Black woman from Southern Mississippi, struggling with losing her mother, with pregnancy, and with systemic racism surrounding these events and her whole life. “There are multiple traumas that she is trying to figure out the reasoning behind. And there are big systemic reasons [behind these traumas], but my characters are also wrestling with all of this on very personal levels,” Ward explained.

Exploring the trauma of Black young men and women affected by systemic racism is a key motivator.

Sing, Unburied, Sing tells, in part, the dark story of the Black inmates of Parchman, a penitentiary in Mississippi, through Ward’s characters Pop and Richie. Ward said she crafted Richie’s narrative to make visible what black inmates endured. “Writing about him became, in part, an endeavor for me to bring him, and children like him who lived and suffered through that, into the present consciousness,” she said. “I wanted children like him, who had been erased, to be able to tell their stories and live for my readers in the present.”

The author also discussed her own journey to come to terms with trauma.

In Ward’s 2013 memoir The Men We Reaped, she tells the stories of five young men whom she lost over the course of five years, including her brother, who was killed in a car accident. “Part of what I was attempting to do in the writing of the book was to assert that they existed— that they were here, and they were important, and their lives had value and had worth,” she said.

“My characters, when they are sharing [their] stories about trauma, that is what they are trying to communicate as well,” she said. “The erasure of everything that I found precious and important about the people that I loved in The Men We Reaped — I think my characters feel that too.”

Storytelling has been therapeutic not only for Ward’s characters, but for Ward herself. “The process of writing the memoir led to a deeper understanding of who I was,” she said.

Ward acknowledged that her work can be difficult and heavy, but said a sense of hope is never lost. “That’s at the heart of all of my work, this sense of hope. Because I think that in order to survive everything that I have survived, and everything that my characters have survived, you have to have hope,” she said. “That you can help create change, that there can be a different reality, and that which exists now is not it, and is not the end.”

Romy Hildebrand is a third-year Communication major at UC Santa Barbara. She is a Web and Social Media Intern for the Division of Humanities and Fine Arts.