By Faith Harvey

With a variety of media available at our fingertips, humankind can today access information crucial to answering many of life’s fundamental questions. But this has led to “information overload,” often making it harder rather than easier to cope, says UC Santa Barbara scholar Wolf. D. Kittler.

“I’m in an awkward reeling of too much information and too little information,” Kittler told the inaugural session of the latest Interdisciplinary Humanities Center lecture series, ‘Too Much Information.’

Kittler is a professor in UCSB’s Germanic and Slavic Studies department, specializing in Greek literature, history of art, science, technology, media, and critical theory.

Wolf D. Kittler, professor in the Germanic and Slavic Studies department at UC Santa Barbara, presents the inaugural lecture for the Interdisciplinary Humanities Center’s new series: Too Much Information.

He recalled for a virtual and in-person audience how he grew up in Germany before the era of instantaneous messaging. Many lacked telephones and Morse code was still in use. Kittler remembers that while writing his doctoral dissertation, he had to navigate the more than 10,000 books and articles related to his subject, Franz Kafka. He read pages and pages of books in his study, even cutting and pasting passages from books by hand.

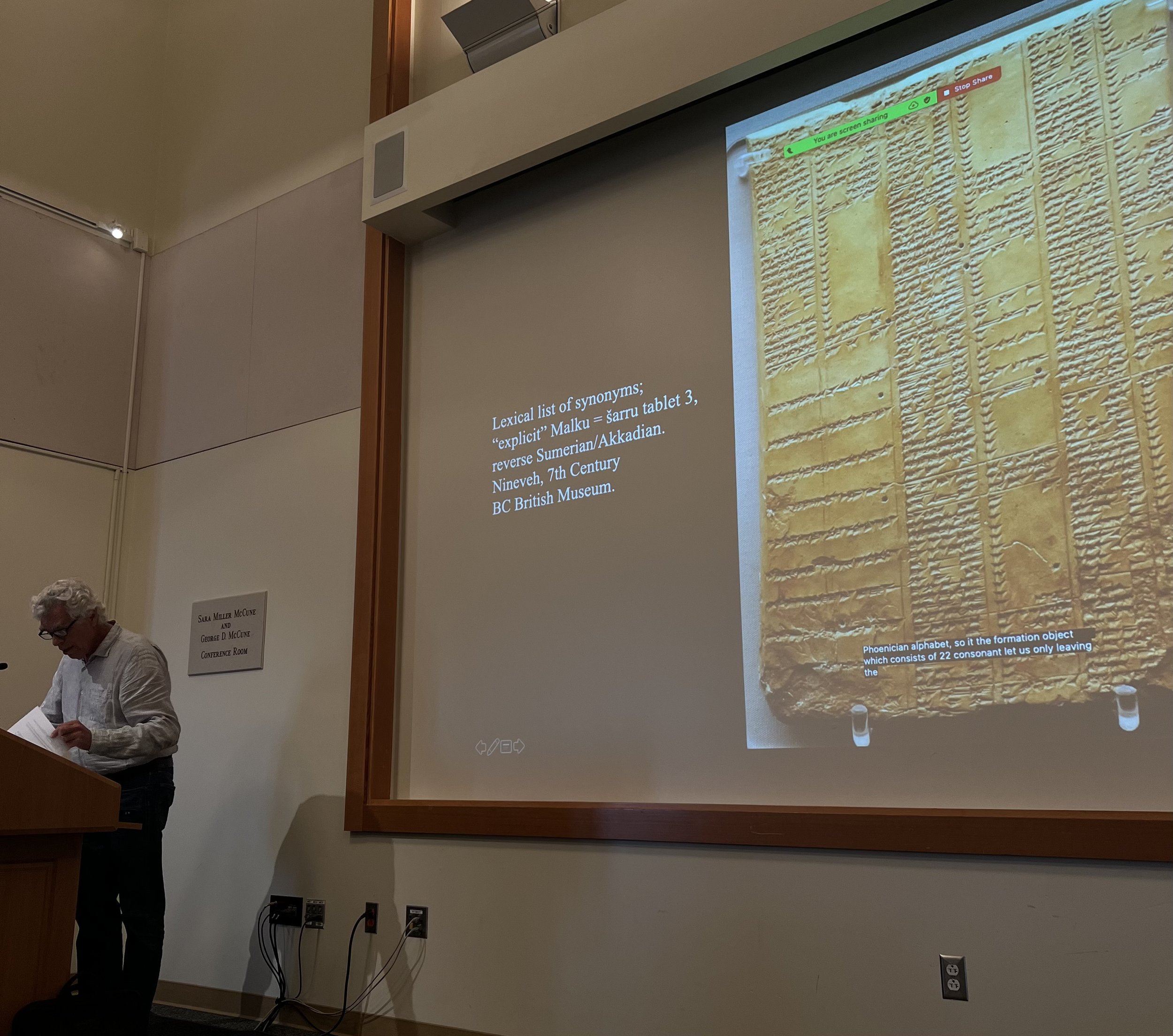

In his talk, Kittler went even further back in history, showing an ancient Mesopotamian clay tablet, the 'Lexical list,' inscribed with cuneiform listings of how to use semantics and words. It’s the oldest known Mesopotamian text, marking a transfer to writing from the era of oral recitation, such as when orators would narrate of Homer’s epics. Writing, he said, became “a remedy for forgetfulness.”

Kittler identified the tablets as the only thing generations could pass down to teach the art of reading and writing, at a time when reading determined one’s status in the hierarchy of Mesopotamian society.

Wolf. D Kittler, professor at UC Santa Barbara, displays a Mesopotamian ‘Lexical List’ during his inaugural lecture for the Interdisciplinary Humanities Center’s new series: Too Much Information.

To go from a history of oral recital to today’s social media era in a matter of three millennia is “a miracle,” he said.

Even after the arrival of the printing press, data retrieval was far more difficult than it is today. Kittler used a timeline to show a progression from biblical annotations, to footnotes, to page numbers, to a printer’s name and publication date, to tables of contents and more.

Yet with books everywhere, in a supposed paradise of knowledge, accessing useful information was already becoming more complicated, Kittler said. Historically, knowledge has relied on what an individual does with the information at hand, he stressed. “The mind is more powerful than ink on papyrus.”

Kittler pointed to Google and other search engines that today allow us to retrieve data in seconds, and to pay for information to guide our lives – on everything from diet to relationship advice to entertainment. These sites are “not the enemy,” he said, admitting he used Google several times while composing his talk.

But instead of broadening our horizons, the current abundance of information has actually funneled us into narrow niche communities, Kittler suggested. He called this a “natural consequence” of abundant information that keeps people pigeonholed to one subject.

Humankind has “inherited all-embracing knowledge,” but people should explore their passions, hone in on their craft, and embrace collaboration, Kittler urged. At a time when technology is sure to spread information even wider in ways we cannot predict, Kittler reminded his audience that in the end, the mind is the key to turning information into knowledge – philosophy will win out over bits and bytes.

Faith Harvey is a third-year student at UC Santa Barbara, majoring in Communication and pursuing a minor in Professional Writing. She is a Web and Social Media Intern for the Division of Humanities and Fine Arts.