By Amelia Faircloth

At the turn of the 20th century, the United States saw a boom in immigration, as people from around the world traveled west in hopes of work and opportunity. At its peak, Japanese immigrants made up only a small portion of the population, yet campaigns arose to exclude Japanese Americans from U.S life, a UC Santa Barbara audience was told.

In a recent UC Santa Barbara IHC event, UC Berkeley English professor Andrew Way Long discussed his forthcoming manuscript, “A Queer, Queer, Race: Orientations for Early Japanese Literature.”

In a recent talk for the UCSB Interdisciplinary Humanities Center, UC Berkeley English professor Andrew Way Leong examined Japanese American literature in the context of these acts of exclusion—specifically, the Immigration Act of 1924.

In the 1920s, the United States government imposed severe restrictions on immigration from non-European countries, backed by the Act. These restrictions effectively ended Japanese immigration for 12 years, damaging the ability of Japanese Americans already here to realize their dreams for the future.

“In the 1930s, entering into the period right before World War II, orientations for thinking about early Japanese American literature might have been future-oriented through ideas of reproductive futurity,” Leong said.

Barring Japanese immigration meant that many Japanese immigrants put their hope for the future and building a permanent Japanese American community in the hands of their American-born children. But as Leong pointed out in his talk, focusing so much on offspring left out Japanese Americans who wished to pursue a non-traditional family structure, such as those in queer relationships or perpetual bachelorhood.

Academia has long classified the different generations of Japanese American immigrants with specific terminology. The term “Issei” represents the first generation while the term “Nisei” represents the second generation, or the generation born in America, Leong explained.

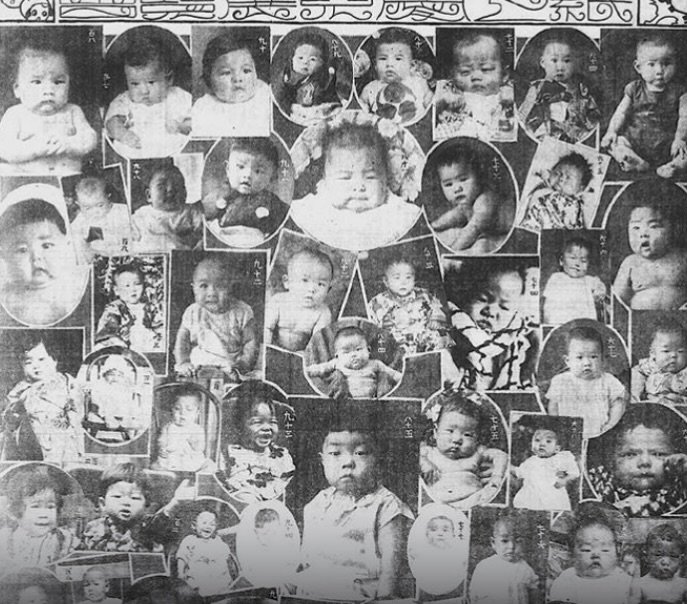

UC Berkeley professor Andrew Way Long showed newspaper images celebrating all the children born in 1930 to show how important reproduction was for Japanese immigrants looking to settle in the US.

Although generational terms of Issei and Nisei have dominated scholarship on Japanese American literature, Leong’s manuscript “A Queer, Queer, Race: Orientations for Early Japanese Literature” tries to deconstruct that generational terminology.

To examine how frequently the words Issei and Nisei showed up in literature and media, Leong turned to online databases.

“From this research, I found that these terms, Issei and Nisei… really did not operate except in academic jargon, or jargon of elites,” Leong said.

He also explained that generational terms fail to distinguish between community and offspring, mixing up the “ideational conception of futurity and the reproductive conception of biological children.” By imagining the future as something achieved through having children, the generational term of Nisei excludes non-traditional family structures, like queer and mixed-race relationships.

But by looking into the literature of early Japanese American immigrants like Shōson, Sadakichi Hartmann, Arishima Takeo, and Yoné Noguchi, Leong observed the author’s hopes for other, less traditional, familial structures.

“People might have been interested in pursuing alternatives to the ideas of family possessiveness,” Leong said. “They might have also been interested in earlier 19th century ideas of perpetual bachelorhood, or envision bohemian or alternative possibilities for their soldering in the United States that did not involve the family formation and permanent settlement.”

Amelia Faircloth is a fourth-year UC Santa Barbara student majoring in English. She is a Web and Social Media Intern for the Division of Humanities and Fine Arts.