By Cece Stage and Emma Danzo

Award-winning science fiction writer Ted Chiang spoke about his short story collection Exhalation at a recent event co-hosted by the UCSB Library and UCSB Arts and Lectures. Photo by Alan Berner.

We tell stories to make sense of the world, and science fiction offers a way to explore complex moral dilemmas, award-winning author Ted Chiang told a UC Santa Barbara audience last week.

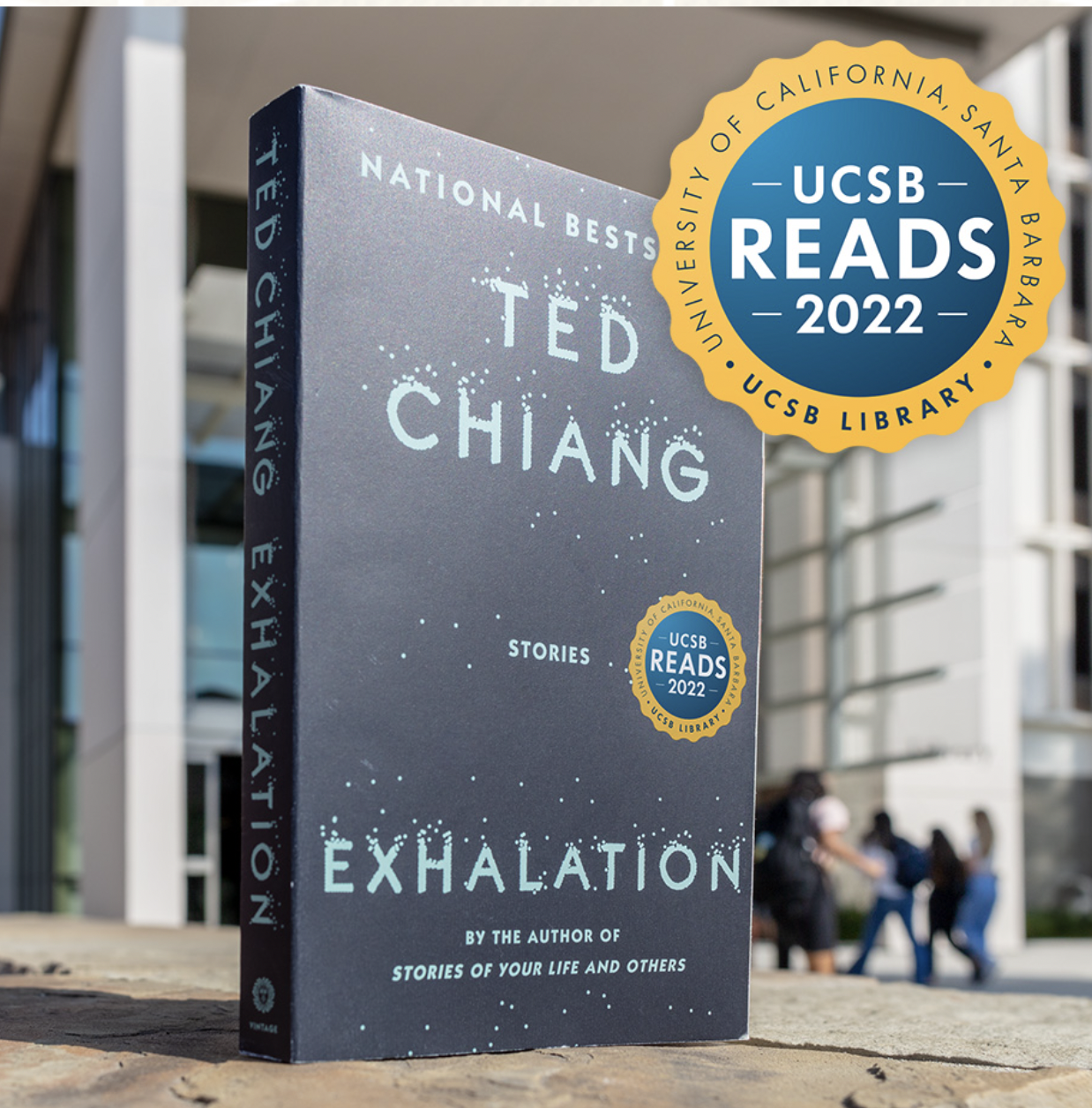

Chiang discussed his science fiction writing and his short story collection Exhalation, which was this year’s selection for UCSB Reads, a program that has for the past 16 years brought the campus and the larger community together over a single book. Chiang’s book poses philosophical questions of free will, memory, and technology in futuristic worlds.

“Science fiction offers a way to turn these philosophical questions into something a wider audience can appreciate,” Chiang said, stressing that storytelling works best when abstract ideas are grounded in emotion.

Since January, UCSB Reads has given away 2,500 copies of Exhalation. At the culminating event of the UCSB Reads program, Chiang spoke to a Campbell Hall audience on the complexity and shortcomings of memory. It was co-sponsored by the UCSB Library and UCSB Arts and Lectures.

Chiang said technology has restructured our cognitive functions, particularly our memory, and he predicts this will continue. He introduced the concept of “lifelogging,” the practice of video recording our entire lives to look back on, to reference at times when our memory falters. Lifelogs, he said, could become just as integral as Google has become for us today, serving as a database of personally-accessible information that we could simply Google-search for answers to the questions our brains can’t seem to remember.

Ted Chiang, left, author of the best-selling short story collection Exhalation, spoke about the fallibility of human memory and the idea of “lifelogging” in his recent UCSB Reads talk. English professor Melody Jue moderated the discussion.

Lifelogging, popularized by electronics engineer Gordon Bell, based on the increasing ease of — and decreasing cost of — storing data, might be the future of memory. Now that we have access to almost any information at our fingertips, “technology has impaired our ability to remember,” Chiang said.

He cited studies and real-life examples, such as how GPS is wiping out our navigational abilities. The ‘contacts’ app on our phones also makes younger generations less likely to remember their own phone numbers than older ones. As modern technology has reduced our need for aspects of memory, lifelogging will help as our dwindling memories rely more on technology to supplement our imperfect cognitive functions, Chiang said.

He presented lifelogs not as a solution to our worsening memories, but rather as cognitive evolution. He likened the personal use of digital lifelogs to how advances in technology moved society from oral tradition to writing, which many people were against at the time, claiming that “it will implant forgetfulness in their souls,” as Socrates put it.

In his talk, Chiang said our memories purposely forget, as a way to tell ourselves a story about life.

“Scientific enterprise and religion are connected in that they are both the pursuit of wonder and awe.”

“We don't want facts to get in the way of the stories we want to tell,” Chiang said. Our memories selectively forget, tweak, and misremember the past to make a palatable story. He suggested that a lifelog could become a useful tool of self-improvement allowing us to remember instantly and accurately and be more consistent in our beliefs and actions. Lifelogs could serve as fact-checkers to evaluate our statements, helping hold ourselves accountable to the truth. Moreover, lifelogs could help solve crimes, maintain accurate historical accounts, and serve as introspective prompts to understand ourselves better.

Ted Chiang’s short story collection Exhalation was this year’s selection for UCSB Reads, a yearly program that brings the UCSB campus and Santa Barbara community together through literature.

Chiang argues that polishing up inconsistencies — better recalling the truths of the past— could have moral value as well. Just as education allows us to understand the history of the US as more complex than the version we learn in elementary school, so could a more accurate memory lead to a more moral human life. Chiang stopped short of endorsing lifelogging, instead leaving the crowd ponder the implications.

English professor Melody Jue then conversed with Chiang about Exhalation and its film adaptation, Arrival. Audience members lined the aisles to ask Chiang questions that ranged from his creative process as a writer to his views on free will versus determinism.

Chiang, an atheist, said he nonetheless uses religion as a lens through which to understand the universe. “Scientific enterprise and religion are connected in that they are both the pursuit of wonder and awe,” he said. To make science and philosophy engaging, the author says he ties these topics into “emotional storylines,” using enthralling characters and plots to communicate complex speculative ideas.

“The facts of the matter aren’t the only things that matter. The way it makes us feel also matters,” Chiang said.

Cece Stage is a fourth-year English major and Emma Danzo is a third-year Communication major. They reported on this event for their Writing Program course Digital Journalism.