By Elin Fredlund

Touch is an important tool for emotional relief that can be incorporated into our indoor environments, architect and designer Felecia Davis said in a virtual seminar recently hosted by the Media Arts and Technology graduate program at UC Santa Barbara.

Pennsylvania State University Architectural design professor Felecia Davis combines architecture, computing, and psychology in her project FELT.

“People feel and change material with their bodies. In that process, the materials change them,” Davis told the virtual audience.

Davis has degrees in architecture and engineering as well as a PhD in Design and Computation from M.I.T. She is an architectural design professor at Pennsylvania State University and director of SOFTLAB which develops responsive textiles, such as those in her latest project FELT (Feeling Emotions Linked through Touch). Davis has also taught at Princeton, Cornell and the Swedish School of Textiles.

With the FELT project, she creates computer-controlled textiles that can transform their texture in response to environmental stimuli. The textiles include small motors that can be turned on and off, which change the fabric as people are touching them.

Each fabric she showed was about one by two feet and had other pieces of fabric sticking out of it that moved with the computer programming. The moving fabrics were based on the pelts of animals. The feathers of a bird, hair of a bear, scales of a snake, and other animals were used as models. Davis’ team first made hundreds of models before settling on one that resembled the feathers on the head of a parrot.

Pennsylvania State University professor Felecia Davis used the texture of animals as inspiration for her recent project, FELT, to create textiles that feel recognizable.

She argued that our brains have already started to shape an understanding of what it would be like to feel these textures, just by looking at the pictures. “One should expect everyone to bring in their own experiences and history and culture into things to make sense of them. Therefore, analogy and memory played a big part in how people felt the different fabrics,’’ she said.

It may sound like science fiction, where a robot’s skin could be designed to feel like a human’s. But Davis said the goal is therapeutic, to create fabrics that are recognizable and make people feel safe, that can be placed on various objects in the home such as pillows, walls and toys.

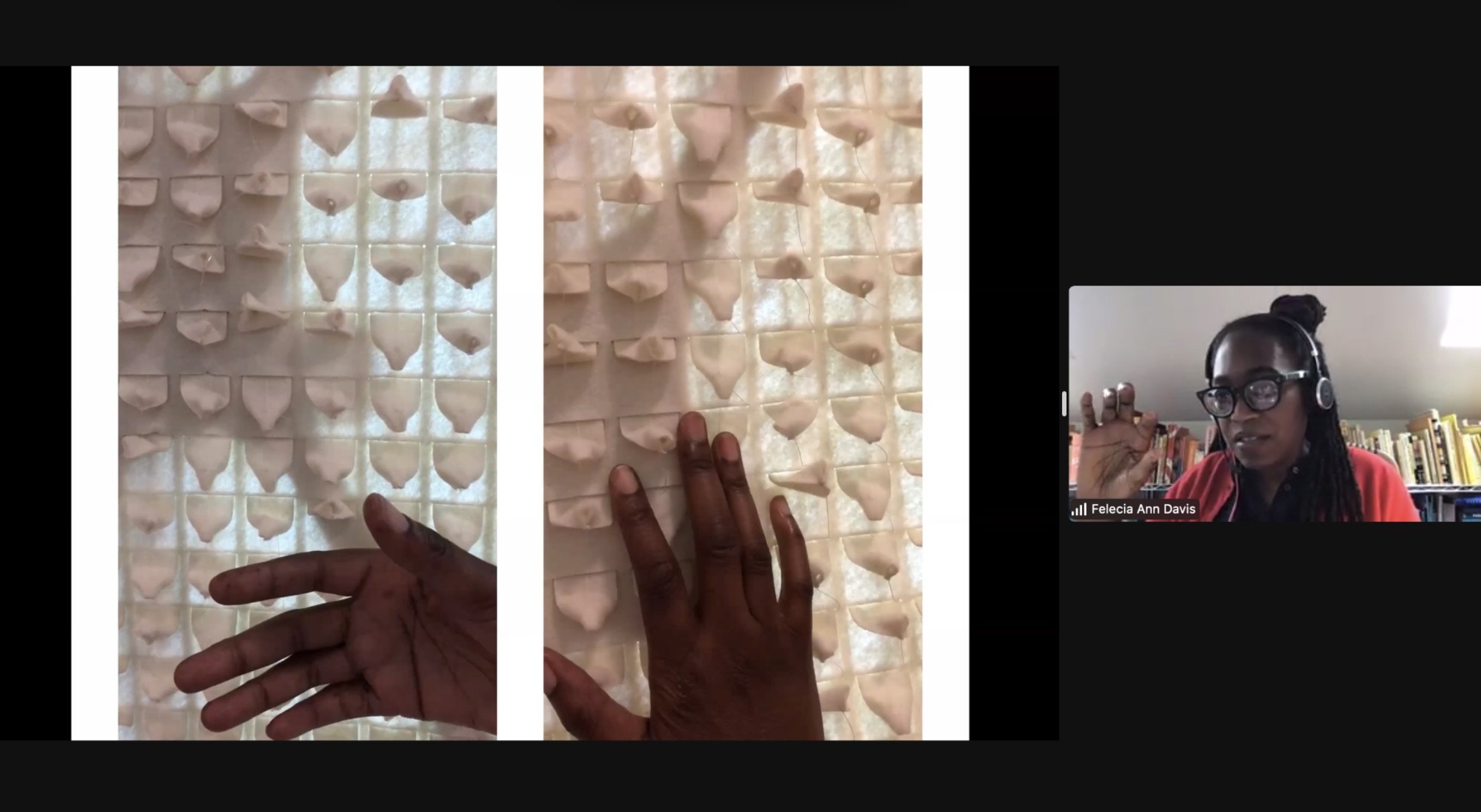

Architect Felecia Davis showed an example of the responsive textile that was used in the project FELT at a recent MAT seminar at UCSB.

Davis believes that responsive textiles can provide comfort for people who are lonely and do not have the ability to express their emotions. Her research study examined human interaction and the textile-mirrored response. This intersection between design and psychology creates a progressive way of looking at what meaning textiles have in our everyday life, she said.

Touch is very different from other senses, such as vision or hearing, because it is more interactive, Davis said. But it is also something we take for granted, almost like air. “You are kind of talking with the material that you are touching. Once you can touch something it changes your perspective of it.’’

This aligned with the findings of her research team at SOFTLAB when trying out the material for FELT with test groups. That involved people both observing and touching these fabrics. Researchers spoke with participants about how the fabrics made them feel. Participants were asked to interact with the fabrics on four occasions. They were to look and then touch while the fabric was still, then they looked and touched while the fabric was active.

Davis provided examples of textiles developed in her lab.

The participants would sometimes have negative associations with the fabric and say it felt uncomfortable when looking at it, but then change it into a positive view once they touched it saying it felt smooth and safe.

Davis said we should look at a textile as a living thing that is mixed, complex and changeable. “I want to bring back softness into architecture,” she said.

Elin Fredlund is an international student at UC Santa Barbara who studies strategic communication in Sweden. She wrote this article for her Writing Program course Digital Journalism.