By Jenna McGovern

Poet and comparative literature instructor Rick Benjamin has urged readers to engage in less self-absorption and make space for compassion for others, in his latest book of poetry, “The Mob Within the Heart.”

“We talk a lot about decentering the human in my class, Wild Literature in the Urban Landscape,” Benjamin said. “It’s very hard for human beings to not center themselves, and so I wanted to think about that with this book.”

UCSB Writing and Literature professor Rick Benjamin marked his 40th year of teaching with the launch of his fifth poetry book "The Mob Within the Heart."

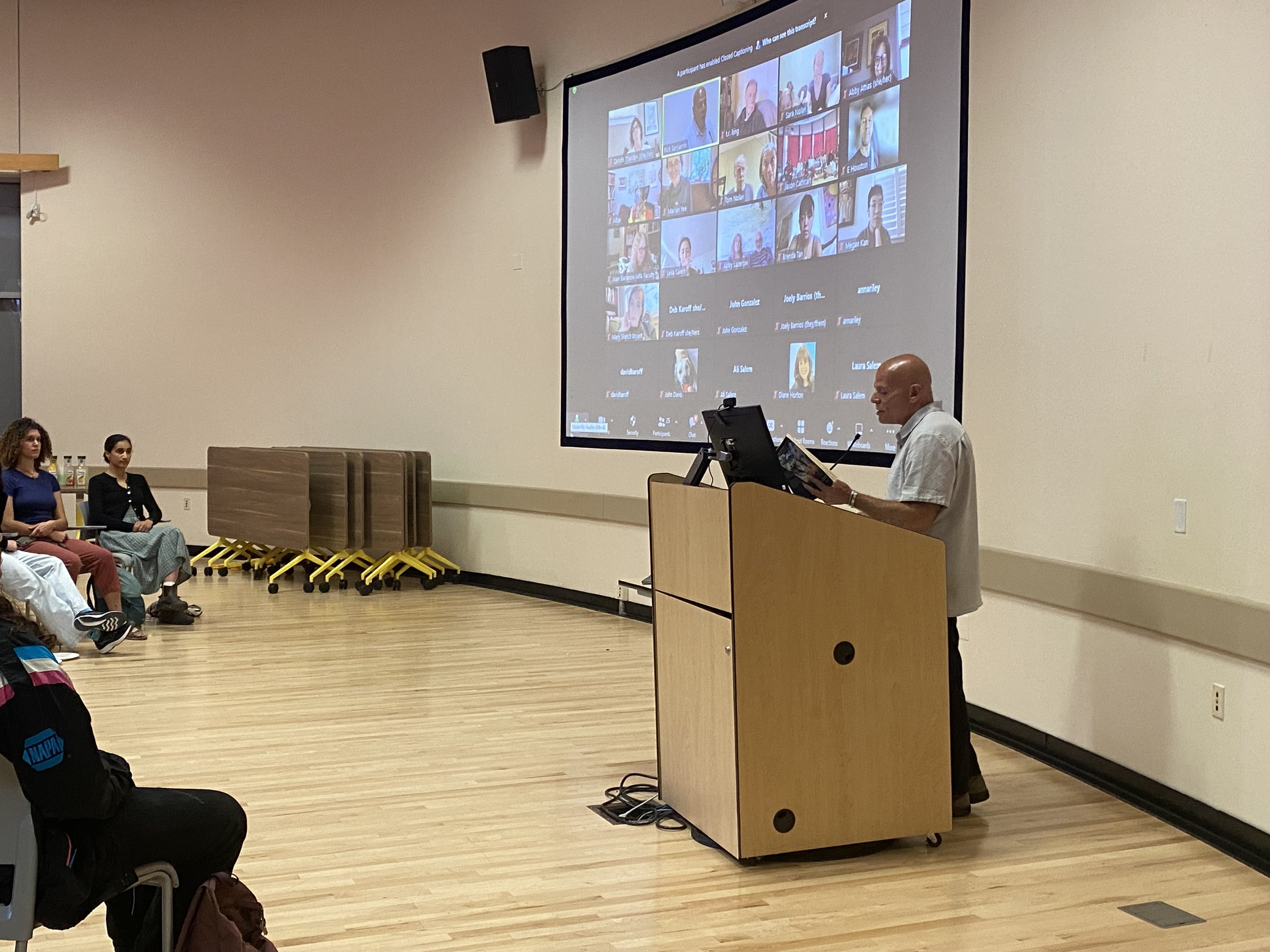

Benjamin read excerpts from what is his fifth book at a recent launch event presented by the UC Santa Barbara student Poets’ Club. Written during the COVID-19 pandemic, it expresses the poet’s feelings about love, political conflict, illness and loss. He describes overwhelming love in his closest relationships and explores the complex responsibilities of being human.

“At the same time, I wanted to think about ways in which we’re constantly avoiding doing this other thing as human beings — which is looking at the shadow self and really interrogating those places inside of us that make us uncomfortable.”

Poetry books written by UCSB Writing and Literature professor Rick Benjamin.

Benjamin dedicated the book to his partner, Margaret Klawunn, UCSB Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs, and he read a poem about their relationship through the lens of a rock-climbing trip they took.

“It doesn't matter what shape we're in, whether or not we make it all the way to the top. Although today, it is worth noting, we will. What matters is each step she takes ahead of me and the way it draws me like a rope, pulls me up toward all of our years together, climbing,” Benjamin read.

“The Mob Within the Heart” details stories from his life and many of the poems are written for his close companions, including his sister, who joined Klawunn at the event. He spoke to an audience of around 50 students, friends and family, many attending on Zoom from as far as Rhode Island, where Benjamin grew up. Benjamin is also the former Poet Laureate of Rhode Island and has taught at UCSB since 2015.

Known among students for his riveting poetry and writing courses, Benjamin integrates local and global ecological challenges and sociopolitical changes into his curriculum. He also extends his teaching to elders at a local assisted living center, the Boys and Girls Club of Goleta, and youth detention facilities.

One of the 10 poems he recited from his book is about the candle pod acacia tree, native to Africa, which Benjamin likens to the parts of the self that people hide, much as these trees have defense mechanisms to repel giraffes. “Spirit resists being eaten when someone else's hunger says dangers nearby. Best to throw off scents from your darkest places, the ones that put off even you. Maybe later, you'll be ready for that new becoming, right when it takes you in,” Benjamin recited.

He introduced two of his students, Maya Salem and Jason Cathcart, who each shared four of their own poems prior to Benjamin’s reading.

“Rick takes hours out of his personal time to sit with students individually and help revise poems. Naturally, I had to jump at the opportunity to help him plan this event, just to give back a slice of the effort that he gives to the community,” said Cathcart, president of Poets’’Club.

Benjamin also read three poems by other authors that he felt illustrate a shift away from egotism. “Birdfoot’s Grampa” by Joseph Bruchac, is the story of a man moving dozens of toads out of danger in the roadway. “I kept saying, ‘You can’t save them all. Accept it, get back in, we’ve got places to go.’ But, leathery hands full of wet brown life, knee deep in the summer roadside grass, he just smiled and said, ‘They have places to go too,’” Benjamin recited. He also read Bruchac’s “Cantile” and Naomi Shihab Nye’s “Hidden.”

UCSB Writing and Literature professor Rick Benjamin reciting poems from his recent poetry book "The Mob Within the Heart."

Benjamin often begins his poetry classes and orations with reading the works of others. “I think that it's the job of poets to keep poetry circulating, and not just their own,” he said.

Another poem Benjamin recited described the hospitality and altruism he encountered on a trip to Egypt. “Someone with nearly nothing to spare prepared this chicken and now offered it to me before feeding her own family, stirred by nothing but kindness to offer food first to a stranger, one who almost choked on the blessing,” he read.

Benjamin has been teaching for nearly 40 years and his current students range in age from five to 99 years old. “Pretty much the reason why I teach is to keep on putting myself in the company of others with whom I can think and learn,” he said. “And so, I feel very privileged to be here and I feel privileged to be here with my students.”

The cover of “The Mob Within the Heart,” features a painting by Oregon-based artist, Abby Lazerow, called “Domestic Terror” which depicts an aggressive interaction between police and protesters, aligning with the book’s title. “There were ways in which I had been thinking a lot about this book as a way of looking at a lot of things that were happening at once in this country,” he said. “I didn’t see it as an activist book, but as a book where I could talk about a lot of different things in the same breath.”

The book title derives from Emily Dickinson’s poem “1745,” which was a name Benjamin had planned for some time. Dickinson’s poem chronicles perseverance in the face of repression. “The mob within the heart, police cannot suppress,” she wrote.

“The Mob Within the Heart” expresses Benjamin’s wonder and frustration with life. “There are ways in which we have all this baggage about being human beings. But none of it’s genuine, none of it’s authentic,” he said. “And if you’re lucky, you get to examine your own blind spots and decolonize your own mind and figure out what’s human and what’s not.”

Jenna McGovern is a third-year Communication major pursuing the Professional Writing Minor. She wrote this article for her course Digital Journalism